Handwriting development

- Vicky Crane ICTWAND

- May 27, 2022

- 22 min read

Updated: Dec 18, 2025

Join me on a journey to eradicate handwriting as a limiting factor. My own research involving reviewing pupil books across the curriculum and analysing pupil data across multiple schools means I have seen first hand, and have hard evidence about just how much handwriting holds back pupil progress, and is particularly an issue for disadvantaged pupils.

I offer three pillars of support: 1) An overview of handwriting research and practical advice for free; 2) You can book a paid 'expertise session' with me to support leaders in your school tasked with reducing barriers to attainment and progress; 3) At a practical level, there is a fully resourced classroom handwriting package of which you can find details at the end of this post.

The importance of developing handwriting, stamina and fine motor skills cannot be over emphasised. The transcription skills (handwriting and spelling) do not have to be a limiting factor for pupils. Teachers can work systematically and utilise research to ensure all pupils can write! Let me try and persuade you...

What published studies say about handwriting:

“Correlation studies have provided evidence that automaticity of letter writing is the single best predictor of length and quality of written composition in the primary years.” Graham, Beringer, Abbott, Abbot & Whitaker, 1997. Beringer at al 1997, Graham, Harris and Fink 2000, Graham et al 2015. There is evidence (Berninger & Hayes, 2012) that early writing skills (learning to write and perceive letters) may affect learning to spell and read words during middle childhood.

'Pupils need sufficient capacity in their working memory to plan, compose and review effectively. This requires transcription skills to be secure. As a result, fluent transcription skills should be a critical focus for the early years and key stage 1. ' Ofsted, Curriculum research review series: English, May 2022.

Compare the impact - pupils with poor handwriting, pupils with good handwriting

Let's start by comparing two pupils. Perhaps you can think of two pupils in your class, one with poor handwriting and one with very good handwriting. How do the two pupils compare for attainment in writing, confidence, stamina?

You can download this image as a PDF document.

What personally drives me to be invested in handwriting

Why am I interested in handwriting : please see video below.

(Note - I needed a removal van to return all the books to schools - just in case you are thinking about carrying out a similar book review. The review of books looked at a wide range of issues, not just handwriting, but that is beyond the scope of this blog post.)

What my own research make stark

In two book reviews a few years apart covering 15 primary schools in Leeds, a disproportionate number of lower ability writers in all year groups had poor handwriting. Since handwriting is not a highly cognitive skill, we must question 'is it handwriting that is holding back progress and, over time, prevents pupils from attaining as highly as peers with good handwriting?' The research tells us how important handwriting is - and not just because of presentation! Recently, a Year 6 pupil asked a visiting secondary teacher (transition event) how important handwriting was and the teacher replied 'not really important'. And you can see how for the majority, this might be the case but not for those for whom handwriting is a limiting factor. It would be interesting for secondary schools to review books of pupils with poor handwriting. Perhaps the teacher is not thinking clearly enough about some of the older pupils who struggle with stamina and content in essay writing and GCSE examinations. Perhaps this illustrates the battle there is in ensuring research information gets to the front line.

And so...handwriting should be relentlessly pursued

Given the importance of handwriting shaping writing development, the foundational writing skill should be explicitly taught and systematically practiced as soon as possible. Even pupils without handwriting difficulties benefit from handwriting practice and handwriting instruction (Santangelo & Graham, 2016). The meta-analysis carried out by Santagelo and Graham reported that handwriting instruction was associated with impressive improvements not only in students' handwriting skills but also on the quality, amount, and fluency of their writing.

Fluent and legible handwriting is necessary factor for developing good writing skills. A number of studies have shown that handwriting interventions can help remove a key constraint on the development of writing composition (Christensen, 2005). Although handwriting might be considered a 'low level' skill (as in it is not overly difficult or cognitively demanding compared to other factors involved in pupils being successful writers), a lack of automaticity constrains the pupils in being able to develop higher-order writing processes (Abbott, Beringer, & Fayol, 2010). Handwriting and other transcription skills, such as spelling, are a necessary lever for writing development (Alves & Limp, 2015; Beringer & Winn, 2006; Graham & Harris, 2000; Joshi, Treiman, Carreker & Moats, 2008).

"We would like to further extend that mechanistic analogy by suggesting that transcription skills can be conceived as the fulcrum of the lever - that is, the place through which, by virtue of its location, load and effort can be judged so to most effectively produce text and ultimately develop writing." Alves et al, 2019.

Poor handwriting skills may result in less legible texts, which in turn influences teachers' impressions about the quality of presented ideas as well as about the writing ability of the student. There is evidence that less legible texts are judged as being poorer quality than more legible texts (Briggs, 1980; Greifeneder, Zelt, Seele, Bottenberg, & Alt, 2012). Reduced legibility is likely to make it difficult for readers to decipher passages and stop frequently to decode the message, or simply neglect less legible portions of the text. Additionally, the extent to which a text is legible may also boost teachers' perceptions about writing ability of the student, with poor penmanship being more likely ascribed to a poor writer.

•Poor handwriting takes up valuable working memory.

•Pupils with poor handwriting often forget the sentence they are trying to write because the working memory is full.

•Pupils with poor handwriting find it harder to think about composition and higher order sentence construction or use new techniques in independent writing – because working memory is full.

•Poor handwriting slows down the process of writing, making text production harder and more laborious. This is turn often leads to pupils not fully answering questions / finishing work. Pupils with poor handwriting need more stamina to finish a piece of writing than those with good handwriting skills.

•If pupils write less, they practice less. This in turn leads to slows progress when compared to peers with good handwriting skills.

•Pupils with poor handwriting tend to get less teacher feedback / more superficial feedback.

•Pupils with poor handwriting have less confidence in themselves as writers. Research shows that confidence is important for progress in English.

•Pupils with poor handwriting are more likely to struggle with spelling (and in younger year groups with phonics progress).

•Pupils with poor handwriting are less likely to be able to read their own handwriting, making self-assessment and editing/revising work more difficult.

•Poor handwriting limits the ability for pupils to engage in meaningful peer assessment.

•Poor motor skills and handwriting can impact on mathematics progress, e.g. ability to align numbers, ability to use a ruler, ability to draw handles on clock faces.

"Many schools do not fully appreciate the processes involved in the acquisition of skills for legible handwriting nor do they make links with progress and achievement." Doug, R 2019.

Free handwriting advice download

You can download a handy PDF of think prompts below:

Reflective questions about handwriting

Question: There is an abundance of handwriting research available. However, handwriting is still a limiting factor for some pupils.

If as a profession we know that poor handwriting impacts on progress in all these ways, why do so many pupils (across schools nationally) have poor handwriting?

If we as a profession have research that tells us what a high impact handwriting session should include, why do teachers (across schools nationally) not follow the advice?

Slow handwriting makes it more difficult for writers to keep pace with the speed at which language is formulated in their minds. This is well exemplified by the seminal finding that, with beginning and struggling writers, spoken texts are usually better quality than written texts (Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1987; Graham, 1990; Hayes & Berninger, 2010). This means that slow writers struggle with the huge asymmetry of production rates between spoken and written languages, as the pace at which they are able to produce speech is considerably faster than the pace at which they can record it. Pupils forget the ideas that they were trying to write and their thought processes are interrupted by the transcription process.

Questions:

Where handwriting is very poor...

•We want to eradicate handwriting as a limiting factor, but, in the meantime, whilst pupils are working on developing their transcription skills, how could you assess pupils’ underlying abilities?

•How might providing pupils with the opportunity to record oral stories (with picture cues or linked to a planning document) help to assess pupils’ ability to structure a story, develop characters, describe scenes, visualise action and develop story ideas? How might this differ from assessing a written piece of writing?

•Do you witness pupils' frustration with their handwriting speed?

•Do you notice pupils making mistakes such as repeating phrases, stopping mid-sentence, repeating words in the work they produce? If so, could this be because their thought process is going more quickly than their ability to write?

Until becoming automatic and fluent, handwriting requires considerable mental resources (Bourdin & Fayol, 2000; Olive & Kellogg, 2020). Attention devoted to the execution of fine-motor movements to produce letters and words means less attention can be allocated to important high-level writing processes, such as idea generation and language formulation (McCutchen, 2000). Indeed it limits the writer's ability to enact with other processes concurrently while transcribing. The high cognitive cost of nonefficient handwriting may additionally constrain the enactment of self-regulated strategic writing behaviours. These behaviours are fundamental for producing high-quality texts.

Questions:

•How might good quality (pupil) planning help to reduce cognitive load for pupils who have transcription difficulties?

•If all of working memory is being taken up with the transcription process, what impact does this have on a pupils' ability to spot their own errors and self-correct as they write?

Poor handwriting, making the process of writing slow, dull and laborious, is likely to lead to writing being a less pleasurable experience. As a consequence, children may lose interest and enjoyment in writing, thus facing a potentially downward spiral conducing to low writing achievement, anxiety, avoidance behaviours, and arrested writing development (Beringer, Mizokawa, & Bragg, 1991; Beringer et al., 1997). Slow handwriting may also negatively affect students' self-efficacy for writing (Limp & Alves, 2013). Indeed, given that young writers consider linguistic and mechanical factors as among the most important ingredients in good writing (Olinghouse & Graham, 2009), slow writers may be more prone to hold negative appraisals of their ability to compose text. Such negative beliefs are commonly associated with poor writing performance (Pajares, 2003).

Questions:

•Which pupils’ self-confidence in writing might improve if handwriting issues were eradicated?

•Many pupils equate good handwriting to being a 'good writer' and lose confidence if their writing is not good. How can we change pupils' perceptions of 'what makes a good writer'?

•How can we help pupils to help themselves and take more control over their ability to write fluently?

•How do we help pupils to recognise that investing in handwriting development is so much more than just presentation?

Design of handwriting sessions

How long should handwriting sessions be and how frequent?

You can't short cut the process. The research leads to the conclusions that 15 minutes of deliberate handwriting development every day (plus other opportunities to write) is required! One of the problems is that not enough class time is devoted to very carefully structured handwriting sessions and that handwriting sessions stop too early. I would recommend handwriting sessions are run in every year group where handwriting has not reached a high standard of clarity and automaticity and/or where stamina is an issue or where handwriting may be impacting on composition and logical development of ideas or pupil confidence. We must remind teachers of older year groups that improving handwriting has been shown to have a positive impact on overall quality of writing, and many pupils find handwriting sessions quite therapeutic! The majority of pupils are likely to make gains from handwriting sessions in all primary year groups. Although internationally there is no consensus as to when gains in handwriting end (too many different starting points and differences in approaches), there is research that indicates handwriting speed continues to mature throughout the primary years (e.g. Gosse, Parmentier, Raybrock 2021). That said, it is important for teachers and leaders to keep monitoring pupil progress and have informed discussions about handwriting. Longitudinal studies would suggest that it is likely at some point in upper KS2 (around end of Year 4) that handwriting quality (e.g. size, shape, spacing, legibility, pressure) reaches a plateau (however some such studies may show a lack of gains because the schools have stopped delivering handwriting as a taught session) but speed and automaticity continue to increase. Since research is mixed it would be sensible for leaders to use professional judgement in Year 5 by assessing pupils' speed and accuracy of handwriting to determine as which point handwriting sessions might switch from being every day to whole class interval training, personalisation for target letter/joins, and intervention groups. If handwriting is being taught systematically from EYFS upwards, over a few years, less time will be need to be devoted to handwriting sessions further up the school. As classroom time is at a premium, we have to manage the time strategically!

Assessing handwriting:

Teachers can assess handwriting by reviewing pupil books and by carrying out simple assessments as shown below. Teachers can also ask pupils to write as much as they can for 1 minute and compare number of words to accuracy and precision of the handwriting. (Although we want speed and automaticity to improve - this should be steady gains. We are not seeking speed at the expense of legibility what we want is an improvement in both!)

Should the design of handwriting sessions be different in EYFS?

There is a growing body of research about emergent writing and we have to keep in mind how all the different elements come together to create competent young writers. As well as vocabulary, language development, oracy, imagination, creative play, knowledge of stories and other genres, understanding of print to convey meaning...etc., there are quite a few handwriting subsets in play (recognition of the letters of the alphabet, being able to visually discern the difference between the letters such as the letter 't' and the letter 'l' (which might seem obvious to us but not to a very young child), the letter names, the matching of capital letters and lowercase letters, phonics and phonological awareness, early spelling strategies). We would expect pupils to be exposed to the alphabet on many different occasions during the school day, e.g. during reading/writing phonics sessions, when reading, when exposed to print, in handwriting sessions. Deliberate handwriting sessions are just one part of a bigger jigsaw.

Deliberate handwriting sessions in EYFS should have the same key ingredients as sessions aimed at older pupils - emphasis on quality formations, cue cards, live modelling and self-evaluation. (Sitting and producing 20-50 letter 'a' formations of varying quality without live modelling and cue cards is a very ineffective way to bring about improvements - and unfortunately, I have witnessed such sessions on more than one occasion). There needs to be an emphasis on really looking at the shape of the letter (drawing attention to differences / similarities of other letters). The sessions should allow for there to be repeated exposure to the shape of the letter. In addition, teachers should take the opportunity to reinforce letter name and sound, uppercase and lowercase visuals. However, it is important to balance very deliberate handwriting sessions with general encouragement for pupils to write, draw and express themselves. (Quite often there can be a whole story behind what appears to be a few scribbles)! We don't want to create fear or a need for perfection. Learning to be better at passing the ball or dribbling should not stop me from playing football. I just need to realise that by learning and improving these skills, they will contribute to my improvement as a footballer and ultimately it is unlikely that I can become a great footballer without foundation skills!

EYFS colleagues should take all steps possible to ensure pupils learn the alphabet. You can't write a letter if you can not visualise it! There is a great deal of research on this matter (please do get in touch for support). There are some activities which are effective / ineffective with developing alphabet recognition. You can also read more on the issue of the alphabet on the blog post 'Struggling with phonics?' https://www.ictwand.online/post/struggling-with-phonics In addition, EYFS leaders should take note of Ofsted's advice about using dictation in phonics sessions to utilise the crossover benefits of writing / transcription skill development / phonics.

Should handwriting sessions be part of phonics sessions or separate?

I would argue that phonics sessions should include writing (be that as part of one big session or two smaller sessions), but I would argue that handwriting development is slightly different and therefore should be in addition to and not instead of writing phonic sessions. First, let me try to explain why writing should be part of phonics sessions. First, in observations of pupils I have seen many examples of pupils not being able to write the letter/word because they could not visualise the letter or letter combinations. It doesn't matter how many times an adult sounds out a word or models orally the /h/ or the /p/ in 'hop' if you can not visualise what those letters look like - you still can not write the word. However, display the letters or letter combinations on the screen and many of the same pupils can read the word. They are a slightly different skill set and activate different parts of the brain. Pupils can sometimes have difficulty writing because more time is spent on the reading elements than on the writing of letters/matched words in phonic sessions. We should therefore have a balance and include writing words. Ofsted have equally suggested that pupils who have difficulty with phonics may need more opportunities / interventions that focus on writing dictated words and there is some research that would suggest the motor and sensory nature of the writing task will help pupils to make grapheme/phoneme connections stick and therefore lead to improvements in both reading and writing. The writing sessions as part of phonics should concentrate on the sounds produced,, writing, letter recognition and testing out the security of recall for the grapheme to the phoneme - including speed of recall. If we also stress the pen trajectory, physical movements, quality of the letters, joins, etc., we are in danger of cognitive overload. (That is not to say that we ignore quality altogether in phonics writing sessions, but rather we are mindful of what we want to achieve). Instead, give pupils two bites of the cherry (with suitable gaps between to ensure concertation levels are achievable). In the handwriting sessions pupils will have further exposure to the grapheme-phoneme correspondence and teachers can even incorporate phonic matched words or the words used in previous phonic session into the handwriting session, but the focus in the handwriting sessions should be on quality formations, cue cards, live modelling and self-evaluation. Writing sessions as part of phonics will improve handwriting - because it is a form of practice - but not as effectively as sessions which deliberately focus on handwriting. Well informed teachers can run both and draw on the bi-directionality of activities.

Cursive or not cursive in EYFS?

Although there is mixed research outcomes on starting / not starting with cursive, I think I would favour print in EYFS with the move to cursive in Year 1. (When to exactly start cursive is a matter for professional judgement - but perhaps don't leave it too long into Year 1. In Ofsted's latest publication on English curriculum research they recommend print rather than cursive at the start of the writing process and point out that this is stated in the National Curriculum.)

How to view handwriting sessions beyond EYFS

Think about daily handwriting sessions as skills building and writing at other times applying / practice. To start with, the letter formations and words produced in handwriting sessions will be better than pupils can manage when writing at other times. Reassure pupils that this is normal. It will take some time for the practice to lead to automatic handwriting. As pupils progress through the handwriting sessions they should move from individual letters, to joining one other letter, and then to short words (as appropriate for the pupils, e.g. linked to their stage in phonics, words they use regularly in written pieces) and then the 100 most common words. This can then extend to 300 most common / spelling lists / topic words etc. Writing short words that contain the target letter help pupils start to see the impact of handwriting sessions on their everyday handwriting. (It is useful for teachers to have the same font as the handwriting being used with pupils. This can then be used in creating models of key words for pupils / spelling lists etc).

Advice about the structure of the daily handwriting session:

Sessions of 15 minutes every day.

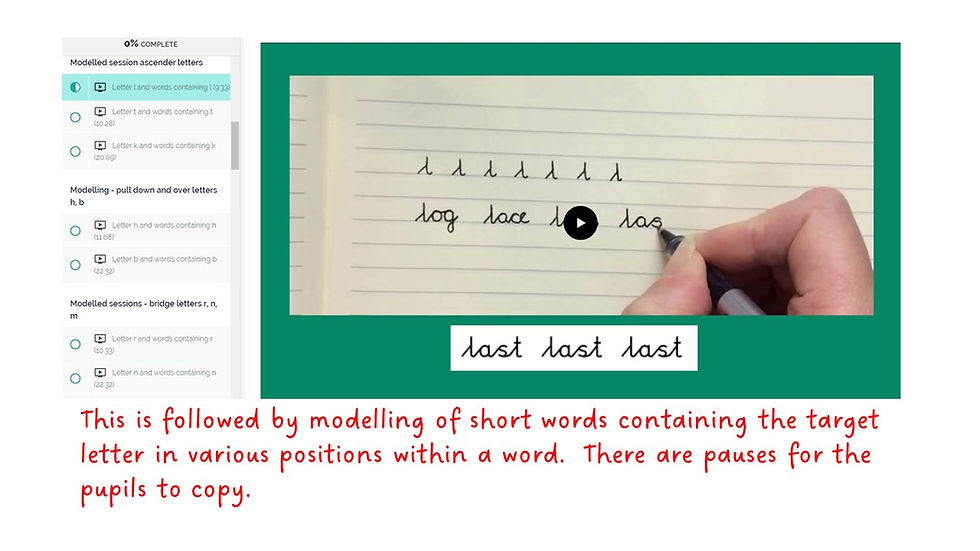

Focus on quality careful formations. (Not 50 letter 'a' formations of dubious quality, but 5-8 careful formations). Pupils should be looking carefully at models and cue cards trying to create a good rendition. After initial formations, move to short words containing the letter, and then perhaps back to a few final individual letters.

Introduce groups of letters (if you use a particular scheme they usually suggest an order - see example below). Discuss similarity in letter shapes and formation.

Pupils need to see repeated modelling.

Voice instructions aloud whilst modelling (live or recorded).

Pupils need to focus on looking carefully at individual letters using a visual cue card. If your scheme uses cue cards with arrows for directionality - even better. It is useful for cue cards to be printed and on the desk next to the pupil.

Pupil needs repeated practice with live/video modelling and a cue card. Eventually they will be able to write accurately from memory, but to improve handwriting make sure they can see the visuals.

Pupils need feedback (positives and correctives) and to self-assess (e.g. circle the two best letters formed, set their own targets, allow tracking of development). Quite a few research studies have found self-assessment to be a key ingredient in effective handwriting sessions. You might provide pupils with good and bad examples. Ask pupils to evaluate the examples (e.g. poor shape, too faint, not on the line, person hasn’t started in the right place for forming the letter) to help them improve their self-assessment skills.

Opportunities to write words. Tracing can be useful for additional practice, e.g. spelling lists, poems, name, key words, phonics. But it is the focus on modelling and careful practice that has more impact. Tracing has only been shown to have limited impact. Therefore perhaps trace then write the word would have greater impact.

Pupils may need additional support with lowercase q, j, z, u, n, k – in one study these six letters accounted for 46% of omissions, miscues and illegible attempts.

Download this bullet point list as RAG activity (Red, Amber, Green).

FREE DOWNLOAD RAG LIST

Research indicates that writing letters has higher impact than tracing letters. The writing experience activates the fusiform gyrus, parietal cortex, and premotor cortex, which is often reported in adult and child studies of reading (Booth, 2007). Thus, writing seems crucial for establishing brain systems used during letter perception and, by extension, reading acquisition.

It would be advantageous to link handwriting practice to phoneme manipulation activities, spelling, tricky words and syllabication - as looking carefully at the letter combinations within words leads to greater automaticity in reading. A network is developing in the brain that supports letter writing and perception and the role of forming letters in learning to recognise the words in learning to read.

Suggested order for handwriting development:

1. Counterclockwise c based letters: a o c e d g q

2. Pull down letter / ascender group: I, k, t, f

3. Pull down and over / ascender group 2: h, b

4. Pull down and over letters / lower bridge: m, n, r, p,

5. Curvy letters / dot and bowl: i, j, u, y

6. Zig zag letters: v, w, x, z, - could put e in this group

Lined paper:

A question I am sometimes asked is about the line height. There are a variety of different options and teachers may need to experiment to find the height that works best for their year group. At the moment, I can not say definitively on this issue.

Spelling:

You might be interested to know that the research of Gosse, Parmentier and Raybroeck in 2022 found that pupils were more likely to have spelling issues with words that were harder orthographically to write (for example words that contain a letter where the child has to make an abrupt change pen trajectory, such as the letter 'r' compared to words that contain all curvy segments, such as the letter 'c'). For older pupils, perhaps they could particularly practice trickier to write words to improve spelling as well as handwriting!

As well as handwriting sessions, pupils may require other support such as the development of gross motor skills and fine motor skills. I have not covered these areas in this blog. If you would like more details on these elements, please do get in touch.

A package of support

In December 2020 I was working with a school on addressing stamina issues and the discussion naturally turned to handwriting. I suggested that the school should record teachers modelling handwriting to use in class and potentially at home. In January 2021, another period of lockdown started and schools moved to remote learning. As teachers were stretched in trying to support pupils during this time, I thought one of the things I could do was to record the videos. It started as quite a small project - just record all the letters of the alphabet. However, as I worked to ensure it matched the knowledge I had gained on the most effective ways to teach handwriting, the project grew as did the number of man hours I invested! In the end, I recorded repeated modelling of individual letters and also common letter joins, short words containing the letters, the 100 most common words and some extra videos for tricky letters. I created additional worksheets and ensured there is a list of the 300 most common words and year group by year group spelling lists in the matching font.

The videos are far from perfect - sometimes they are shaky being made at home, sometimes the modelling is not perfect. My black pen ran out and I couldn't get another one for quite a while. But, I think this is part of the charm of the videos. It makes the development of handwriting more real and more accessible for the pupils and reassures them that it does take time and effort to learn a new handwriting style.

I was particularly pleased that the school were able to move from 'advice' about developing handwriting to daily action because the online package made it so easy to deliver. With a short training session, anyone could deliver daily handwriting sessions. The school made a commitment to all teachers using the system. Reports of confidence boosting from older year groups started flooding in! The handwriting sessions were having an impact not just on the writing of younger pupils, but there was evidence that the system supported pupils at different ages. The package could be used by everyone in class all at the same time, as an intervention, as a home learning scheme. Teachers / pupils could move at a pace they felt appropriate and aligned to the needs of their class. (I am sure it would be useful to have research on pace.)

Could your school benefit from access to an online package for handwriting?

Teachers in Year 1 started using the videos when pupils returned from the second lockdown in March 2021.

The school I was working with when I created the handwriting course were using the Debbie Hepplewhite scheme. I have not made a comparison to other cursive styles. Some pluses with the scheme are:

The scheme of work is offered by Debbie Hepplewhite at a very low cost.

The joins are easy to form.

Teachers have said the instructional patter for the formation of letters is simple.

You can purchase a font to accompany the scheme for teachers to use in creating their own lists and worksheets.

Free cue cards are provided in a variety of formats.

There is a print version as well as a cursive version.

You can purchase my online videos to accompany the scheme :-). I have recorded live modelling of all letters, the 100 most common words, short words linked to each letter, extra sessions for tricky letters. There are printable worksheets for additional practice.

There is a separate system for Year 5 and 6 pupils and schools who purchase the main videos can have free accounts so that target pupils can access resources at home at work at their own pace.

If you purchase my online videos you will also need to purchase Debbie Hepplewhite scheme for the school.

Teachers have told me how easy it is to use and feedback has been extremely positive.

"The handwriting is still going from strength to strength and it's even noticeable on display boards around school. What a difference the programme has made!" AHT

"After only a few short weeks we have seen the impact. At parents evening, one of the parents commented that the work looked like it was written by two different pupils there had been so much improvement!" Year 5 teacher

After Year 5 and 6 independent practice "I've had a queue of children at my door this week so proud of their progress!" DHT

Video advert: https://youtu.be/d_Fz5SJFwoI

Special offer package : £700 (+VAT): (this is a one-off payment - no need to renew each year, you will have access as long as the package is available - which I hope will be a significant number of years).

Included in the cost:

1 hour meeting with English leader and any other leader in school as appropriate to implementing the programme (via zoom)

Login accounts to the online videos and resources for teachers and TAs (up to a 3 form entry school included). Additional accounts can be added.

Login accounts for up to 30 target Year 5 and Year 6 pupils to a home learning version of the programme. Additional accounts can be added / negotiated.

Note - the schools must purchase the Debbie Hepplewhite scheme and font - which is a nominal fee.

There are no workbooks. Pupils write directly onto paper or a handwriting book. You can download and print worksheets linked to the videos for extra support for pupils or as extra practice.

Whilst some schemes may promote jazzy pictures and cartoons, this focuses on efficient and effective practice without the frills. Whilst teachers often worry handwriting can be boring, in fact many pupils find the quiet purposeful task almost like a mindfulness session and have enjoyed the chance just to focus on one process rather than the complexities of some of the tasks they face during the day! "Visiting teachers looking in on classrooms have asked if the pupils are having a test because it is so quiet and pupils are concentrating so hard."

Or, if you do not need support, you can go straight to the purchase option. Buy online or your school can pay by invoice. Get in touch for details.

FOLLOW THE LINK BELOW: You can watch more examples to see if it is something that would be right for your school by clicking 'preview' on the teachable course page.

Questions not yet answers:

I will continue to explore the published research alongside outcomes from schools using the online package of handwriting to try and find answers to quite a few questions I still have. I think research needs to switch from trying to prove handwriting is an issue to supplying more answers about ensuring all pupils are fluent in handwriting. I am not a researcher, but perhaps I will have the opportunity to work with one in the future.

References

Alves, R. A., Branco, M., Castro, S. L., & Olive, T. (2012). Effects of handwriting skill, output modes, and gender on fourth graders’ pauses, language bursts, fluency, and quality. In V. W. Berninger (Ed.), Past, present, and future contributions of cognitive writing research to cognitive psychology (pp. 389–402). New York: Psychology Press.

Abbott, R.D., Berninger, V. and Fayol, M. (2010) Longitudinal Relationships of Levels of Language in Writing and between Writing and Reading in Grades 1 to 7. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102, 281-298.

Berninger, V., Mizokawa, D., & Bragg, R. (1991). Theory-based diagnosis and remediation of writing disabilities. Journal of School Psychology, 29, 57–79.

Berninger, VW, Vaughan, KB, Abbott, RD, Abbott, SP, Rogan, LW, Brooks, A, Reed, E & Graham, S 1997, 'Treatment of handwriting problems in beginning writers: Transfer from handwriting to composition', Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 89, no. 4, pp. 652-666

Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1987). The psychology of written composition. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bourdin B., Fayol M. (2000). Is graphic activity cognitively costly? A developmental approach. Read. Writ.13, 183–196. 10.1023/A:1026458102685

Carol A. Christensen(2005)The Role of Orthographic–Motor Integration in the Production of Creative and Well‐Structured Written Text for Students in Secondary School,Educational Psychology,25:5,441-453.

Doug, R. (2019) ‘Handwriting: Developing Pupils’ Identity and Cognitive Skills’, International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 7(2), pp. 177–188.

Graham, S. (1999). Handwriting and spelling instruction for students with learning disabilities: A review. Learning Disability Quarterly, 22, 78–98.

Graham, S. (2006). Writing. In P. Alexander & P. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 457–477). Mahway, NJ: Erlbaum.

Graham, S., Berninger, V., Abbott, R., Abbott, S., & Whitaker, D. (1997). The role of mechanics in composing of elementary school students: A new methodological approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89, 170–182.

Graham, S., Berninger, V., Weintraub, N., & Schafer, W. (1998). Development of handwriting speed and legibility. Journal of Educational Research, 92, 42–51.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. (2000). The role of self-regulation and transcription skills in writing and writing development. Educational Psychologist, 35, 3–12.

Gosse C, Parmentier M and Van Reybroeck M (2021) How Do Spelling, Handwriting Speed, and Handwriting Quality Develop During Primary School? Cross-Classified Growth Curve Analysis of Children's Writing Development. Front. Psychol. 12:685681.

Joshi, R Malt & Treiman, Rebecca & Carreker, Suzanne & Moats, Louisa. (2008). How words cast their spell. American Educator. 6-43.

McCutchen, D. (2000). Knowledge, processing, and working memory: Implications for a theory of writing. Educational Psychologist, 35, 13–23.

Olinghouse, N., & Graham, S. (2009). The relationship between the writing knowledge and the writing performance of elementary-grade students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 37–50.

Pajares, F. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and achievement in writing: A review of the literature. Reading and Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 139–158.

Santangelo, T., & Graham, S. (2016). A comprehensive meta-analysis of handwriting instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 28(2), 225–265

Willingham, D. (1998). A neuropsychological theory of motor skill learning. Psychological Review, 105, 558–584.

Handbook of Writing Research, Second Edition. Guilford Publications.

Comments